My angel mother died three nights ago. She was at last peaceful, drifting out of several days of semi-consciousness following a steady decline from what was by then a rapidly spiraling dementia, compounded in her final days by a COVID-19 infection that may well have produced a stroke. Jeanne Patricia Eaton Rabey, gone now, permanently gone, beyond even the increasing levels of disappearance that we, her surviving family, had witnessed over the last few years, escalating progressively after the death of my dad, her husband, Frank Rabey.

Some who view this whole shamble of human experience far differently than I do, perhaps under some sense of a divine light that guides them, may contend that my mother has gone indeed now to be an angel, but they would be wrong, so terribly wrong.

My mom, you see, has always been an angel; her death does not in any way enter into it.

Throughout my adult life, I have often said it, never joking: I am a mama’s boy. That nothing compares to my mother. My perfect mother, in all her vast and sundry imperfections.

I am also, not inconsequentially, an unbeliever, an atheist. Yet my mother, who, across a long life battling an intractable personal darkness, grasped at every opportunity for the light, is to me what people often mean when they use the word “angel.” Infinitely caring. Unselfishly giving. Inherently kind.

what follows …

… is not meant as an obituary. Call it a eulogy, if you like. Just realize that we really don’t eulogize the dead. We eulogize what we, who are left behind, have lost in their passing.

I need now to tell you what I have lost. It seems to me at this moment to be the very world itself.

Though let me first back up here. Let me start where it may well seem that I should not, as you may be tempted to interpret the words to come as something other than a celebration of a soul held dear. Please don’t make that mistake. Life is complicated; death is easy. Stay with this at least for a bit, if you will.

My mother, you see, was often not there when I was young. I do not mean just that I was a latch-key kid for several years, as indeed I was, with both parents working and older sisters off conjuring up whatever trouble they could find, and me parked alone on living-room floors, first in San Antonio, Texas, my home, mostly, until age 9, and then here in North Carolina, watching Mod Squad and Star Trek reruns on TV.

Because my mom was also not there many times, even when she actually was.

She was plagued across her life by an often debilitating depression, diagnosed early on, wrongly, it seems now, as manic-depression, with a prescribed lithium regimen that she bristled against, and later, applications of electroshock therapy – shock treatments – which I have been led to understand were sustained, and severe.

Among my most wrenching childhood memories is finding my mom out of her head in our Greenville, N.C., kitchen one afternoon after school, with her ping-ponging from unsettling laughter to gasped weeping, and my sister Marlyn doing her damndest to keep me from pointing out the tidy pile of empty Schlitz cans atop the open trash. Which I did anyway. Which I regret to this very day.

For my mother, in her advanced anxious state, having her youngest see this was, I believe, like having me prick open the disconsolate bubble of her life, with all the vast oceans of hurt abiding within her immediately pouring forth. She was devastated, dropping to her knees, a fountain of human sorrow.

It was the first time I had ever witnessed such consuming anguish in another human being, and to have it be my own mother hurt me in ways I have been trying to come to terms with ever since.

Yet I ultimately saw very few of these breakdowns myself; I was too young. My older sisters, however, both experienced years of this, often emotionally paralyzed by it, while I know from later conversations with my father that he was utterly overwhelmed at times on how to navigate it. My mother’s behavior grew for a while so tenuous, so reckless and unhealthy, that my career-Army dad, not long after leaving for Vietnam to serve as a lab technician in a MASH-style hospital, was brought home on permanent family medical leave. I was then 3 or 4 years old.

As an awkward little girl, who grew in her late teens into a strikingly pretty and charming young woman, my mother lived through her father, Tiffany Eaton, 20 years my grandmother’s senior, enduring a massive stroke that left him, for the remaining decade of his life, a vegetable, languishing in an upstate New York VA hospital, but for his inert body, all but gone. This solidly middle-class family was reduced to barely scraping by, my grandmother’s income as a clerk in a local candy store.

And then my mother’s sister, Marlyn, an almost iconically beautiful child (whom my own oldest sister is named for), succumbed to polio at age 12.

My grandmother, Gladys, perhaps understandably, grew bitter, and increasingly caustic, taking to a faithful regimen of alcoholic self-medication, an untenable position from which to parent even a remaining single child, and she indeed could not rise to meet that challenge. How well I remember my deeply disquieted Grandma, her half-glass of Riunite red always near at hand, who loved me like she thought I was her own son, while having left her youngest daughter believing it was she, not my mother’s older sister, who should not have survived childhood.

My mom shared this withering impression with me when I was not long an adult, during a period when she had again plummeted into the darkest depths of herself. She carried that wretched guilt with her the entirety of her life.

Now, if you believe at this point that I have painted here some unflattering portrait, or that I have portrayed at all a simple victim, or if you feel at all uncomfortable that I have shared perhaps what you feel a family should not at such a tender moment as a parent’s passing, I apologize. Not for what I’ve written, mind you. Because it needs for me to be written.

Because:

In my own early 30s, I was compelled, through the shut-up-and-listen-to-me insight of my sister Michele, to finally confront my own depression, which had bedeviled me by then for years. It went on to ruin my first marriage, because I let it. And it pushed me to contemplate, in very clinical terms, that which only my unwillingness to accept anyone else as able to care for my then two beloved cats can now account for my still being here to write this. As in it got pretty damn bad for me for a while.

It was also as if a curtain had been lifted on how I saw my mother. I had always viewed her as fragile, a victim prone to breaking. Someone I felt, in my blundering way, that I had to protect, as if I possibly could.

But no. No. One of us, as I finally learned over the fraught years to come, was a true fighter, forever getting back up and forcing her chin out against such indignities as might come next. The other of us, mired so often then in the rotting mental funk of himself, was viewing her from down on the mat, where he’d buckled bloodied again, out of his own willful blindness, and his persistent failures to even get his fucking gloves on right.

Which is all to say that I began to recognize an abiding heroism in my mother. She took some terrible tumbles into the dark well of herself, battling not only her body’s insidious chemical assaults, but also a past that all but demanded its own raft of mental suffering in her future.

There are, among those talismans invested with the power to change that I remember so well from childhood: the hand-sized books of affirmations, set atop bedside tables and in little wicker baskets in bathrooms, words meant to lift a soul in need. The monthly pamphlets of religious verse bracketed by prompts to draw from them the inspiration to ignite joy, their covers often soft-focus pictures of praying hands. The simple, unadorned Christian icons, set in personal spaces where a solitary pilgrim could see them without involving others who might have been otherwise inclined.

My mother was deeply, and quietly, devout; she never proselytized, never. After her initial failed forays to involve her kids in church services, she made her faith entirely her own, her later-life Sunday mornings given over to broadcasts of Robert Schuller’s Hour of Power, watched often in private, on her bedroom TV. It’s an irony I still marvel over, that my father was himself a very studied unbeliever, something he did not feel the need to announce, but which he also did not hide.

He and my mother were together 60 years, increasingly devoted to one another, a wonderfully mismatched pair of ever-quibbling mourning doves.

these are some facts

>>> That my mother graduated from high school in 1952.

>>> That she worked when she was younger at the long-gone Farmer Fannie Candy Shop on North Union Street in Olean (as I believe did my grandmother).

>>> That she met my dad, then an Army recruitment officer back from a combat tour in Korea, when he was stationed in her hometown Olean, N.Y., in the upstate.

>>> That she became a nurse.

>>> That she and my dad married Sept. 21, 1957.

>>> That they had daughter Marlyn in 1959, then Michele, in 1961, and finally your belabored narrator, in 1966.

>>> That they moved around a bunch, as military families do, Colorado, Arizona, finally Texas, until my dad’s Army retirement in 1975, and his second career as a university professor, which landed our family in North Carolina.

>>> That my dad died of a faulty ticker, Sept. 26, 2017, age 85.

>>> That my mom followed not even three years later, the evening of Jan. 5, 2021, my sisters at her side. She was 86.

these are some memories

How my mother just loved Johnny Cash … how she adored the beach, especially Topsail Beach, N.C., where she would lie on the sand for hours, tanning deep brown, a stark contrast to her normally fair complexion … how this petite woman of obvious northern European heritage crafted buttery onion-slathered homemade pierogies that rivaled those of my dad’s late sisters, my wonderful Rusyn aunts … how she could set out to dust a shelf in the den and soon be sidetracked in her efforts, to where maybe an hour later you would find her in the kitchen, baking cookies, oh, those sugar cookies, and what I wouldn’t give now … how no stray or abandoned pet that ever crossed her path was not then certain to join our family, to live out its days in devoted care … how she was endlessly volunteering, helping those older than herself who had met some misfortune, to navigate their lonely struggles of twilight living … how she could be so funny, so goddamn funny, these perfect little zingers coming seemingly out of the blue … how even as the first hints of her own dementia were surfacing, she still loved to dance with my father, as if it was the absolute best thing that could ever be in this world … how in her last months, when she could no longer walk without constant help, I took her on a short trip, an “adventure,” to the quaint Washington, N.C., waterfront, and on our half-hour return trip home, with her visibly worn out from our short foray, she drifted quickly behind glazed eyes into that internal place you could not follow, as I sang along softly to the music I had playing as I drove, believing her on the verge of sleep, only to then turn toward her at one point to find her staring at me. “I love it,” she said, “when you sing.” And then she was soon again gone, trapped back within herself, with me blinking damp-eyed at the few gray-day cars around us … how she had always loved me so very much, even at my own most unlovable.

let us end, then, standing in the sunlight, laughing

My mother’s whole conscious life, even at the onset of her dementia, was spent pulling herself up by her own proverbial heartstrings, such that while I cannot forget those awful periods of aching sadness, I always immediately think of her in the sunshine she brought with her into a room, even if it was dragged in sometimes by her own sheer force of will. If ever anyone had reason to succumb to the ugliness so fundamental to this chaotic human condition, it was my mom, who never did.

She was knocked down plenty, but then just kept trying, kept rising back up, kept fighting against what hurt. Fighting always to give joy a chance to win.

And instead of bitterness, she was kind, so very kind. It is, even beyond her uncanny natural beauty as she aged, the thing people single out most about her – “such a sweet lady,” my one cousin wrote me only just yesterday. How kind, how very kind, she was. This lovely heart. Her heart like an open door.

She turned an internal life rife of anguish into an outward face of decency and compassion, and it was in no way an act. She was truly, quietly remarkable.

My mom, you see, was just good. And so very few people are good – look around you now at this ridiculous world, with its slings and arrows forever flying. My mother, my dearest mother, was good.

In the last months of her life, after it was long since clear she mostly knew me from how I acted toward her – not as her own son, but instead as among those someones who clearly cared about her – there was this one mild autumn afternoon I am unlikely ever to forget, at least until there is nothing but forgetting. My mom was there on a wooden bench on the back porch of my old family home, with Lisa P., her wonderful daytime caregiver, seated then beside her.

Jeanne Rabey, I should mention, loved her some damn sunshine. To the very end, she took such joy in being outdoors, sometimes blanketed against the dogged chill of advanced age, but still with the sun, that lovely skyburst of warming light, bathing her upturned face. It has struck me more than once, how very much like a flower …

I was there in the back yard that day, broken up in mood, visiting the little grave I had recently dug for my Old Blind Boy Kitty, aka Banjo, one of the dearest pets I have ever known – another former stray; go figure – out where my dad had kept his beloved garden, when I walked across to where my mom and Lisa P. were sitting. I was at a distance enough from them to not have on a face mask, as we were well into this COVID nightmare by then.

“Hey, Jeanne Rabey!” I yelled. For years I had playfully called her that, or “Jeannie,” more often even than I called her “Mother”; it was just this silly thing with us. And at first, my mom said nothing, simply looking at me, not betraying any expression.

“You know who that is?” Lisa P. gently prodded her.

Then, after only the slightest pause: “Of course I know who my son is!” And she laughed, that little skittering lilt that even now takes me back to an unburdened sense of childhood.

“Hello, Frank Rabey!”

I gaped at Lisa P., my eyes wide, mouth literally fallen open. She looked back at me, pretty much the same.

I don’t know that being recognized as me has ever meant even half as much as it did right then.

My mother was an angel, my angel. And oh, what an empty place now for this aging, bleak-hearted heathen, straining for the faintest echo of absent wings, in these long, dark shadows of fading wingprints fanning out across the remainder of my days.

<81 post likes from original blogsite>

Comments

A beautiful tribute.

beautiful piece, beautiful

the triumph over tragedy is inspiring, that persistent streak of pain notwithstanding

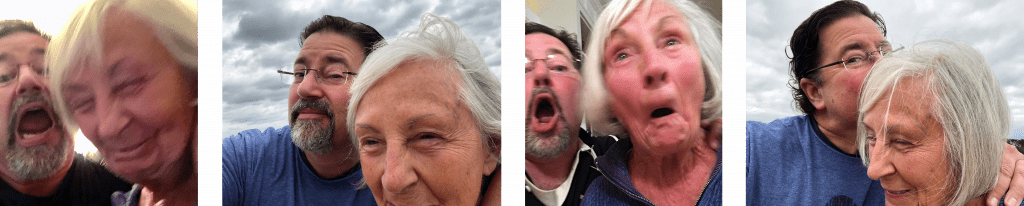

the photos are treasures!

seems like all there is, is gratitude, if you can get there

she certainly was unreservedly grateful for you; what a beautiful thing that is to know

love you!

Beautiful. Like her. Like you. Much Love from here.

This,indeed,bears the mark of an artist that was taught by the essence of life.Thank you good brother for sharing. My condolences.

Be well my friend.

Beautiful. I’d write more but I’m too busy weeping.

Well done Frank. I won’t say much here…you already know why.

Thank you for sharing your love, special remembrances, and facts in such riveting, vivid words and photos of your beloved “Angel Mom ” dear Frank .As I sit here with tears streaming down my face, I just want you to know her kindness and strength and humor and love for others is within you my sweet friend . May you too rise again off the mat of your tremendous grief and live and dance in the sunshine of her precious LOVE

All my Love,

Brenda

Frank, you beautiful soul, I am so sorry for your loss ❤️ ?

jesusgod thank you, Frank.

Beautiful words Frank … the Angel has Risen to be with your dad … I truly enjoyed meeting them … our sincere sympathy.

i had a feeling when you posted from the down-side that this was the case. all i can do is offer condolence and the hug of a friend. beautifully written, sir. heartshapes from an old pal. R

Wow. Thanks for sharing your beautifully written tribute to your amazing mom. I recognize you in her kindness (including kindness to animals), in her sharp sense of humor, and in her goodness. Please take time to take care of yourself as you move through the grieving process. Much love.