I had the tremendous privilege to meet singer Albert Mazibuko the night of the Asheville, N.C., Ladysmith Black Mambazo show that this article was advancing. My life, at the time, was coming to pieces in front of me; my marriage of 11 years was going belly-up, my world set to fundamentally change in the days ahead.

When Mazibuko realized I was the guy who had done the phone interview with him, and written this piece, he hugged me like we were closest family, and it pierced me to my unraveling core, his affection so genuine, and so welcome. I smile to think of it, even now.

Originally published March 3, 2004, in Mountain Xpress| (c) Mountain Xpress, 2004

The revolution will be harmonized

Surmounting hardships great and many, South African traditionalists still raise uncanny voices for change

The first time [I] see the black people and the white people dancing together, and laughing, in my mind, I think: It might be like this in heaven.

– Albert Mazibuko

Albert Mazibuko remembers clearly the day back in the ’70s when he sensed, for the first time in his life, that apartheid might not last forever.

His South African vocal group, Ladysmith Black Mambazo, was performing in the grand ballroom in Johannesburg’s five-star Carlton Hotel, which had been rented outright by a wealthy black man from the Soweto township for his son’s wedding to the daughter of Zulu royalty.

“This was the first time for a black person to stay in that hotel,” Mazibuko, 55, explained by phone in his soft, sweet, heavily accented voice. “You were not allowed to even go into the foyer. In my mind, I think: I might be dreaming to be in this place here.”

Because the only way a black person could then legally overnight in Johannesburg was if he or she were in jail.

The wedding celebration drew thousands and continued for two full weeks. Afterward, Mazibuko recalls, all the papers featured government proclamations that no such integrated social gathering would ever take place in South Africa again.

“Because the white people were in together with the black people,” he elaborates. “It was the first time for me to see the black people and the white people dancing together, and laughing. In my mind, I think: It might be like this in heaven.”

And whatever else might be said about paradise, if the angels sing with even half the burnished glory of Black Mambazo, they’re doing well.

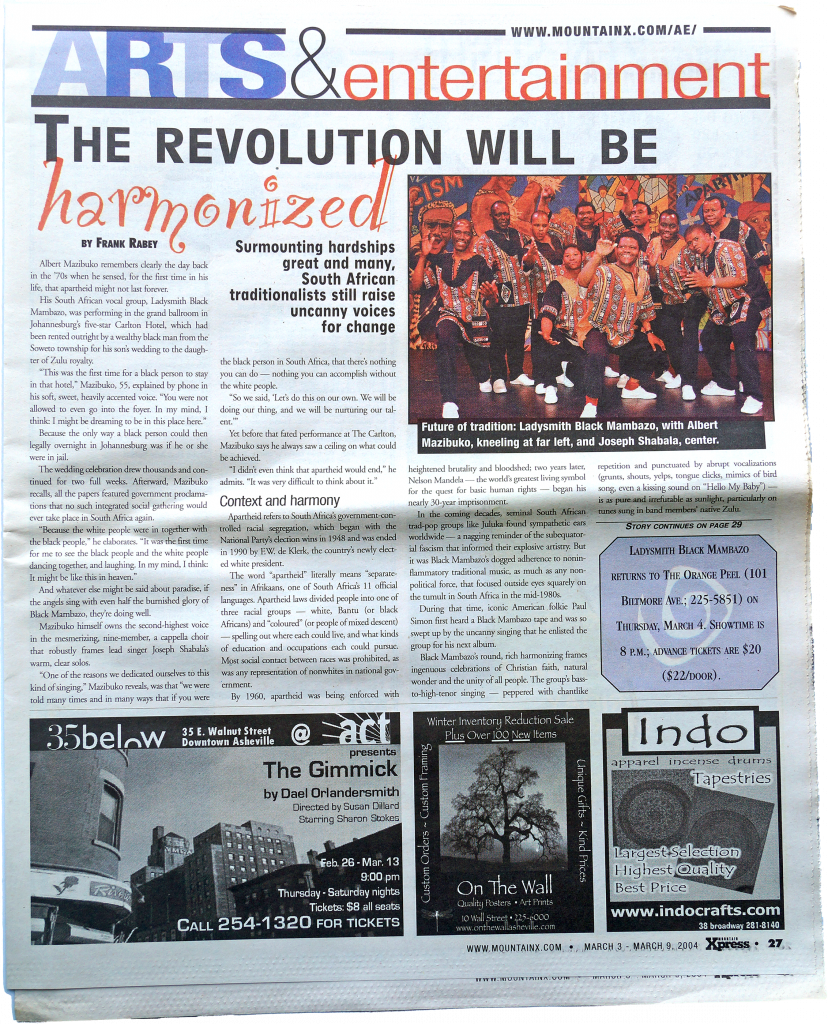

Mazibuko himself owns the second-highest voice in the mesmerizing, nine-member, a cappella choir that robustly frames lead singer Joseph Shabala’s warm, clear solos.

“One of the reasons we dedicated ourselves to this kind of singing,” Mazibuko reveals, was that “we were told many times and in many ways that if you were the black person in South Africa, that there’s nothing you can do – nothing you can accomplish without the white people.

“So we said, ‘Let’s do this on our own. We will be doing our thing, and we will be nurturing our talent.'”

Yet before that fated performance at The Carlton, Mazibuko says he always saw a ceiling on what could be achieved.

“I didn’t even think that apartheid would end,” he admits. “It was very difficult to think about it.”

Context and harmony

Apartheid refers to South Africa’s government-controlled racial segregation, which began with the National Party’s election wins in 1948 and was ended in 1990 by F.W. de Klerk, the country’s newly elected white president.

The word “apartheid” literally means “separateness” in Afrikaans, one of South Africa’s 11 official languages. Apartheid laws divided people into one of three racial groups – white, Bantu (or black Africans) and “coloured” (or people of mixed descent) – spelling out where each could live, and what kinds of education and occupations each could pursue. Most social contact between races was prohibited, as was any representation of nonwhites in national government.

By 1960, apartheid was being enforced with heightened brutality and bloodshed; two years later, Nelson Mandela – the world’s greatest living symbol for the quest for basic human rights – began his nearly 30-year imprisonment.

In the coming decades, seminal South African trad-pop groups like Juluka found sympathetic ears worldwide – a nagging reminder of the subequatorial fascism that informed their explosive artistry. But it was Black Mambazo’s dogged adherence to noninflammatory traditional music, as much as any nonpolitical force, that focused outside eyes squarely on the tumult in South Africa in the mid-1980s.

During that time, iconic American folkie Paul Simon first heard a Black Mambazo tape and was so swept up by the uncanny singing that he enlisted the group for his next album.

Black Mambazo’s round, rich harmonizing frames ingenuous celebrations of Christian faith, natural wonder and the unity of all people. The group’s bass-to-high-tenor singing – peppered with chantlike repetition and punctuated by abrupt vocalizations (grunts, shouts, yelps, tongue clicks, mimics of bird song, even a kissing sound on “Hello My Baby”) – is as pure and irrefutable as sunlight, particularly on tunes sung in band members’ native Zulu.

Simon’s mega-hit Graceland (Warner Bros., 1986), featuring Black Mambazo on landmark cuts like “Homeless,” also pushed what’s now called “world music” into the global mainstream. Sundry small record labels soon sprang up to serve the overnight fascination with everything from bodhráns tombelas, mbaqanga guitar styles to Cajun accordion patterns, sweaty Cuban drummers to swarthy French-gypsy fiddlers.

Yet there was a tempest-in-a-teapot furor over Simon’s employ of the Black Mambazo singers, as South Africa was then under a United Nations-endorsed performer boycott that dated back to 1964. Shortsighted British and American pundits screamed exploitation, immune to the glaring irony in their own protests.

Simon next helmed Black Mambazo’s first U.S. release, Shaka Zulu (Warner Bros., 1987), which landed the luminous singers a Grammy for Best Traditional Folk Album.

So much has happened for the band since.

Black Mambazo, which has now sold more albums than any other African group, has performed for royalty both British (Queen Elizabeth II) and American (Muhammad Ali); worked across genres in collaborations both strained (The Winans) and inspired (Ben Harper, Kermit the Frog); placed songs in countless films (from The Lion King Part II to Spike Lee’s Do It A Cappella); scored original music for Broadway theater (The Song of Jacob Zulu, winner of six Tonys); launched a South African public-school program to preserve the country’s indigenous and traditional music (“South Africa is so rich in music,” gushes Mazibuko); and lent its candy pipes to a delicious Life Savers TV commercial that, if you’ve ever heard it, is still probably rattling around in your head.

But all that’s getting way ahead of the story.

History and healing

South Africa’s popular music is a confluence of indigenous styles and European and American traditions with the politics of oppression.

Isicathamiya (IS-COT-A-ME-YA), the a cappella singing tradition integrated with light-step dance (Shabala calls the latter “tip-toe”), has been largely reinvented by Black Mambazo. This traditional style first arose in secret, in after-hours sessions in the worker hostels, migrant camps and illegal drinking houses (shebeens) that fueled the country’s white-owned, black-operated mines in the early and mid-20th century.

The township choir contests that later developed were the spiritually driven Black Mambazo’s own launching ground in the 1960s (the group was eventually barred from competing, as they consistently beat all comers).

And fittingly, the group’s specific origins have a mystical component.

Joseph Shabala had been performing since 1960 with an isicathamiya choir in industrialized Durban (where a young Mazibuko first heard him, vowing one day to sing with him). But all along, Shabala felt something was missing from the music. Then, in 1964, he began having a persistently recurring dream: a choir of children harmonizing in a manner unlike anything he’d ever heard. Shabala eventually learned to imitate their individual voices.

To reproduce this vision-inspired vocal blend, he returned to his hometown of Ladysmith, assembling and teaching new singers – among them his brothers Jockey and Headman, plus Albert Mazibuko and his cousin, Abednego Mazibuko.

“Open the gates,” translate the words from one old favorite sung in Zulu. “Here comes Black Mambazo from Ladysmith.”

The “black” in the name refers to black oxen, considered the strongest on the farm, while the Zulu word “mambazo” means “axe,” alluding to the group’s felling of opponents in choir competitions.

In the beginning, Black Mambazo was rehearsing almost daily, Albert Mazibuko recalls. Group members would hole up somewhere out of public earshot, so their sound was still largely unknown when they first appeared on government-censored national radio in 1970-71.

Black Mambazo has since seen several transformations, doubling in size and then facing the retirement in 1993 of several older members, who were replaced by four of Shabala’s own sons.

“The young people came with more energy, more strength,” Mazibuko notes. “They have their own dreams, and they have their own style of singing, but they share this dream with us; they share this mission with us.”

Some band changes, however, have been much more difficult, causing Black Mambazo to rethink its very future. Among them are the twin tragedies of Shabala’s brother Headman and wife Nellie being murdered, in 1991 and 2002, respectively.

Yet with each setback, Black Mambazo found itself re-energized by literally working through its periods of greatest grief, Mazibuko reveals.

“That’s why we gave the title to the new album,” he explains, “because our spirit was raised.”

On Raise Your Spirit Higher, released this year on Heads Up International, Black Mambazo sounds as rarified and ecstatically in the moment as ever. And nowhere is that more apparent than when the group performs live, sweeping audiences up in its explosions of spirit, its sparkling joy.

“To share our music with other people,” Mazibuko declares with vivid emotion, “I don’t know why, [but] it gives me so much happiness.

“Every time when I think about singing, I’ve felt that joy inside me, which I don’t know where it’s coming from. It gives me some kind of life. Even if I’m not feeling well, I know that when I start singing, I will be healed.”

Hope in dark places

South Africa’s first post-apartheid election brought Nelson Mandela to the presidency in 1994, a mere four years after his release from prison.

Mandela has often said – as have other former prisoners and once-exiled South Africans – that Black Mambazo’s music, so strongly steeped in both history and hope, was a rock to cling to during those darkest hours. The group performed at the new leader’s inauguration, as they had the year before in Oslo, Norway, at the Nobel Peace Prize ceremony honoring him and de Klerk.

To put it mildly, Mandela is a fan.

“Every time when we’re around – and even when [we’re] not – if he’s doing something important, he says, ‘I want Mambazo,'” Mazibuko relates. “He calls [us] himself; he doesn’t send anyone. He says, ‘OK, boys, I’m doing this – you are available?’

“So, of course, we have to try to make room in [our schedule],” Mazibuko adds with a warm laugh.

“He calls our music ingoma,” the singer reveals. “It means the real music.”

<Page likes lost from original blogsite>