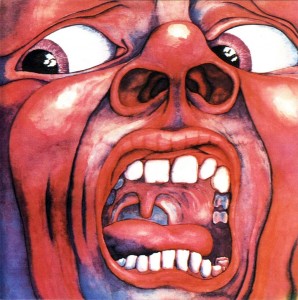

I still remember going to buy a vinyl copy of In the Court of the Crimson King as a teenager, and staring for the longest time down the throat of the screaming red man on the cover. I wanted to love the album, but was only very mildly enchanted by it, mostly just by the stridency of the first cut, “21st Century Schizoid Man.” Beyond that, I found the whole thing kind of noodling and overbearing, though I would never have copped to that then, being musically very hip, and such.

It was the beginning, and the end, of my budding prog-rock fascination. Unless you count Jethro Tull. Which I don’t: Ian Anderson sings way too much about his junk to be considered progressive anything.

Then, when Crimson reformed for the whatever time in the early 1980s with guitar weirdo Adrian Belew, for the trio of albums beginning with Discipline, I was so disconcerted by the music’s interlocking arpeggiated freakishness that I fell into a kind of horrified love with it.

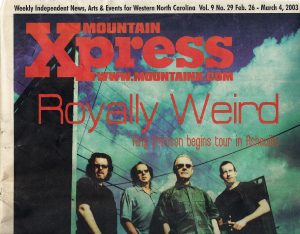

Jump forward about 20 years, and I was pretty excited to get to interview Belew during the 2003 incarnation of the Fripp Circus, which began its tour that year in Asheville, N.C., where I was then living, writing for Mountain Xpress newspaper.

Originally published Feb. 26, 2003 | (c) Mountain Xpress, 2003

Kings of the weird frontier

Prog-rock pioneers progress into heavier territory

Q: Who’s the tougher audience, Robert Fripp or God?

A: Oh, pu-lease! Our Lord never fired Bill Bruford, the drummer’s drummer.

If you opted for the Divine, then you’ve obviously never taken a serious ride on the roller coaster that is King Crimson, the on-again-off-again 35-year vehicle for founding member Fripp’s vision of music as chaotic perfection.

But Fripp, like God, doesn’t talk to the public much. So for breaking news on the Crimson front, turn to singer and second guitar player Adrian Belew.

“I’ve been in both the long-running versions [of the band] now,” Belew noted in a phone interview days before Crimson’s new national tour kicked off in Asheville. “In fact, Robert and I have been together some 22 years now, on and off.

“[That’s] a trophy,” he adds proudly.

Indeed. Crimson has been a recurring game of musical chairs since the band’s beginnings; one fan Web site charts 12 different avatars. And Fripp has frequently given musicians the ax because they weren’t playing to his standards.

Crimson has always been a mixture of virtuosic musicianship, unapologetic pomposity and heavy, heavy weirdness. The band wears its oddity on its sleeve, sometimes literally — which comes as no news to anyone who’s ever stared up the nose and down the throat of the screaming red face that fills the jacket of the trendsetting group’s debut album, In the Court of the Crimson King (Island, 1969).

In those early years, Crimson was just so British, bristling with the musical and personal eccentricities that later came to define progressive rock. But Belew feels the term “progressive” is now too tied to the mid-’70s era of Yes, Genesis and Emerson, Lake & Palmer to be relevant for his band’s ever-progressing sound.

“Perhaps the best term for [our music] is just to call it King Crimson,” he declares, “because King Crimson does sound unlike anyone else.”

What a long, strange Fripp it’s been

Playing with Crimson is a musician’s wet dream — a fact that hasn’t always been volleyed as praise across the band’s lengthy career. These guys know how good they are.

“King Crimson [is] a musical challenge,” Belew observes mildly.

Besides including Bruford in several different lineups (he quit Yes to join the first time), the band also launched the careers of bass player/vocalists Greg Lake (later of ELP) and John Wetton (later of the band U.K. and frontman for ’80s pop phenom Asia), while multi-instrumentalist founding member Ian McDonald went on to form FM-radio stalwarts Foreigner.

But ultimately, Fripp is the Crimson king; the group exists at his discretion.

“He has, to me — and properly so — the right to have the vision of what is King Crimson and what is not,” observes Belew. “We rely on his quality control in that respect.”

When Fripp dissolved the group for the first time in the mid-’70s, it seemed final. When he then assembled the band’s ’80s lineup — himself, Bruford, Belew and session great Tony Levin (bass and 10-stringed Chapman Stick) — he initially dubbed them Discipline before conceding to a band vote favoring the historically charged Crimson name. That incarnation’s first album, Discipline (EG, 1981), is a modern classic.

The group dissolved after two more albums, both flawed but still frequently mesmerizing: Beat (EG, 1982), the first Crimson release to have the same personnel as a previous album; and Three of a Perfect Pair (EG, 1984). Fripp reunited that lineup in 1994, expanding it to a six-piece “double trio” with the addition of two ex-members of David Sylvian’s touring band: Trey Gunn (bass/Chapman Stick) and Pat Mastelotto (drums), also an alum of ’80s schlock-rockers Mr. Mister.

Crimson dropped back to its current four-piece in 1999. This edition — Fripp and American bandmates Belew, Gunn (now on the pianolike touch guitar) and Mastelotto — will release its third album, The Power to Believe (EGM/Sanctuary), on Tuesday.

‘We’re gonna have to write a chorus’

Part of Crimson’s signature style is the music’s spastic dynamic range: Angry six-string squall suddenly evaporates into soft, single-note harmonics; dark textures give way to hauntingly intricate interlocking strands of precision guitar, like aural Celtic knots.

“That’s one thing that, traditionally, has carried through a lot of Crimson records,” Belew agrees with a chuckle. “You play something sweet and beautiful and then — bam! — you play something dark and aggressive.”

Welcome, then, to The Power to Believe.

“It’s got a futuristic, chilling, almost apocalyptic feel to it, which is nice,” Belew observes unironically.

Power, produced by Machine (White Zombie, Pitchshifter), is rarely soft; industrial guitars and threads of dark notes surf atop rolling, thunderous beats, the sound at times so thick it hits the listener like sheets of rain.

“Robert and I decided from the very beginning to write more of a guitar-riff-based kind of music, a heavier-rock music,” Belew reveals, “because it suits the players that we have, especially Pat Mastelotto’s drumming techniques, which are more in that field than Bill Bruford’s were.”

Lyrics are worlds removed from Belew’s pop-y, tender “Man With an Open Heart” (from Perfect Pair).

The words are meant to be ambiguous enough not to distract the listener from the music, Belew explains. The vocalist is “just there to remind you that there’s a song there somewhere.

“For this record, I tried to sing less and have it incorporated more into the thread of the music,” he continues. “So really, you’re listening more to the music than the words.”

And as for the words …

“I guess I’ll repeat the chorus,” Belew howls on “Happy With What You Have to Be Happy With,” his voice electronically distorted. “We’re gonna repeat the chorus.”

Crimson clear, no?

Discipline-arian

Robert Fripp’s rock legacy extends beyond Crimson’s seminal catalog. His reputation is that of a brilliant, reclusive, tyrannical puppeteer yanking his band’s strings from atop a stool in some dark corner.

“Generally speaking, that is an incorrect version of what Robert is like,” counters Belew. “Robert presents to the public a pretty severe characterization of himself; maybe that’s his defense, or maybe it’s something else, I’m not sure. But he presents to me a completely different side. I have a lifelong friendship with him, and a working partnership as guitarist and songwriter that is radically different from that.

“Far from being tyrannical, he’s extremely supportive,” Belew continues. “So I support him in the things that he feels are right for the band.”

For instance, how upcoming live shows will go:

“Right before this interview, Robert appeared in my kitchen — he’s living in [my] guest area downstairs — and told me that he would like to see this incarnation do nothing but new material, from ’99 on,” Belew reveals.

The new stuff is among the band’s most demanding to re-create live.

“It’s difficult,” concedes Belew, adding, “so that makes it fun.”

<Page likes lost from original blogsite>