On Jan. 31, 1995, I conducted a phone interview with Chicago blues great Buddy Guy, for an Asheville, N.C., Mountain Xpress article promoting Guy’s upcoming show down the mountain, in Greenville, S.C. It was only my third interview ever with a professional musician, and it went better than I had any right to expect, but ultimately far worse than I could have imagined.

Three years later, as I was considering content for my creative-nonfiction master’s thesis at East Carolina University in the other Greenville, in North Carolina, I thought almost immediately of that Buddy Guy piece. It had forced me to grow as a writer probably more than any other story I had by then written, in large part due to the great emotional discomfort it went on to cause me.

In the intervening years, I had also come to feel more and more strongly that I had omitted something crucial from it: the full context for an uncomfortable question I had asked Guy. As a fledgling writer back then, I didn’t have near the courage to include that content, because it was about me, not Guy, and I honestly had no hidden HST pretensions. Nor did I likely have the word count to have done so regardless.

Now I had the opportunity to address that error.

What follows is my update to the 1995 story, which you would be hard pressed to find an extant copy of anyway; I kinda suspect I have the only one! I’m glad, actually, as this newer version is easily superior. You’ll notice that even the title has since changed.

Gentleman Blues

Buddy Guy’s Long, Hard Journey Back Home

It may be the most horrible experience I’ve had as a reporter.

While playing back the tape of a phone interview I’d done with a musician I greatly admire, I heard something that made my jaw drop and my stomach sink, something awful. Something I had somehow missed when it originally happened.

I heard myself laughing at a response to one of my questions, thinking the answer wonderfully ironic. I didn’t even realize that the man I was interviewing was crying. It wasn’t at all ironic to him. Instead, it hurt him like hell.

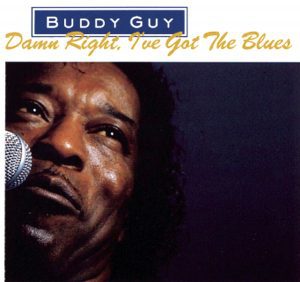

The man on the tape with me was blues legend George “Buddy” Guy.

But let me back up a minute. A little history is in order here: some of his, and a bit of mine.

Guy hails from Lettsworth, La., a small levee town about 50 miles north of Baton Rouge. He was born July 30, 1936, the middle child of five, into the hardscrabble life of African-American rural poverty decades before Civil Rights. His family sharecropped their landlord’s property, and Guy earned extra money working Saturdays on a neighbor’s land, spending that little bit of change on blues records by masters like Howlin’ Wolf, John Lee Hooker and Muddy Waters. Those records, he’s often said, became a living part of him.

While growing up, several of Guy’s best friends were white. One of them, Craig Feduccia, was the son of the Guy family’s landlord. When the two boys turned 18, Guy found that he was suddenly expected to call Feduccia “Mister,” and to no longer socialize with him. For the first time in their relationship, Feduccia was white, Guy black. The experience wounded him profoundly.

Guy left Louisiana (or as he says, “Luziana”) at 8:40 one Monday morning in 1957, already an accomplished guitar player. It was Sept. 23, and he had a $27 one-way fare aboard the now-fabled City of New Orleans, bound for Chicago – home to the successful blues label Chess Records, and to such blues legends as Wolf, Magic Sam, Otis Rush and Guy’s hero, Muddy Waters. It was Guy’s first time on a train, and he sat in the back car with his spartan luggage and Gibson Les Paul guitar, watching the retreating tracks. He didn’t sleep a wink the whole trip.

“I was looking,” he explains, “to meet some of the great people in the music world – like I did meet, Muddy and the rest of them – [who] didn’t come to New Orleans to play, I didn’t ever want to be a professional musician. I just wanted to say [that] I got the chance to see them play in person. And then, all of a sudden, I woke up sayin’, ‘I’m playin’ with ’em!’

“And that was a dream enough for me there,” Guy continues. “I didn’t need nothin’ else to make me reach my goal; I reached it when I shook hands with Muddy.”

But when the train pulled into the station at 63rd and Dorchester at 11:30 that night, no blues legends were waiting there to meet him. The temperature was 57 degrees, and there was a new moon. A wind was blowing up from the south, and the aurora borealis formed a streak across the northern skyline.

A day fraught with such portentous natural imagery cries out for some powerful human event. And it was right there in the newspaper headlines as Guy exited his train: White mobs down in Arkansas were rioting in protest of integration efforts at Little Rock Central High.

Welcome to the Windy City, kid. They say you can’t go home again. Seems like they just said it a whole lot louder.

Like Waters and other seminal blues players who’d made their own treks up from the sweltering South, Guy eventually accommodated himself to the cold, the noise, the grit and grime, the hustle and bustle of the Big Town. Within months of his arrival, he fell in with Chicago’s delta diaspora, making a huge initial impression, and then weathering the petty jealousies of other players who did not share his monstrous gift; the repeated thefts of his guitars; the various blues “revivals” of the ’60s, led by British groups like the Stones and John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers (featuring a young Eric Clapton), that rarely resulted in more work for him; a decade-long stint without a record deal.

He was to be in Chicago for 30 years before his career ignited the public imagination, aided in no small part by Clapton’s offer for Guy to join the all-star 1991 blues-band lineup for Clapton’s 24-night run at London’s Royal Albert Hall.

In 1989, Guy opened his own club at 754 S. Wabash: Buddy Guy’s Legends, now one of the premier blues venues in the world, where you never know when the club owner might choose to sit in. But most people just call the place “Buddy Guy’s.” The “Legends” part is pretty much understood.

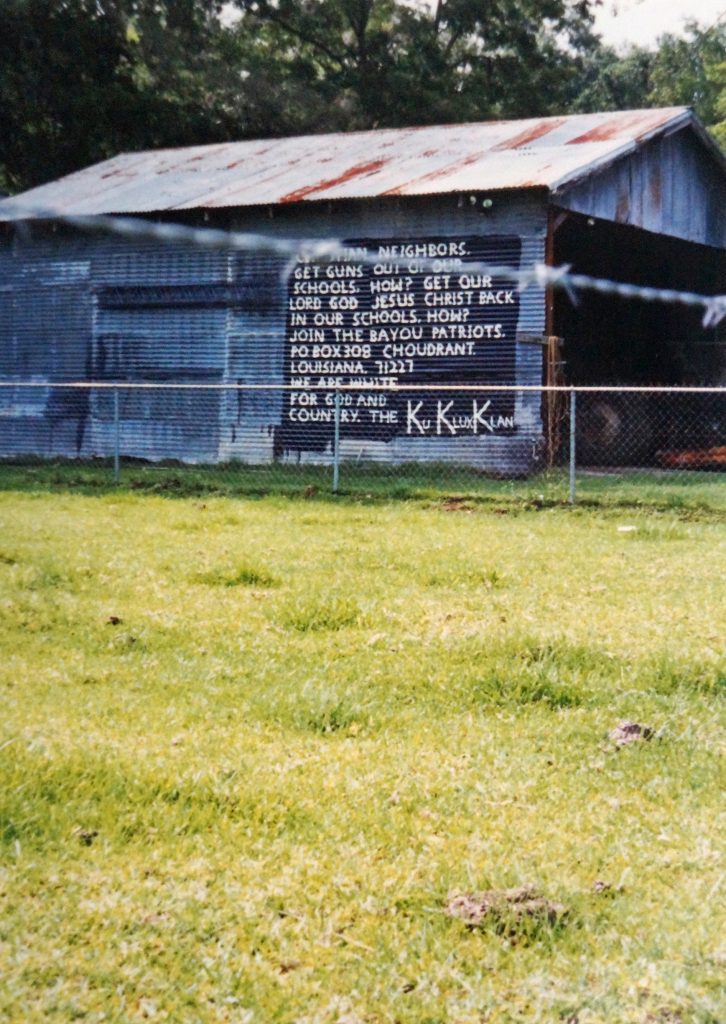

For the first half of 1994, my first wife and I lived in Metairie, La., in a big concrete apartment block just outside of New Orleans. One hot, pretty morning in early June, over a cup of coffee on my fifth-floor balcony overlooking the parking lot where the palmetto bugs amassed at sundown, I read a short Times-Picayune article about a 69-year-old retired school-bus driver named Sam Frederic, who lived in the tiny community of St. Amant, about 25 miles southeast of Baton Rouge along Interstate 10. Frederic had painted a huge sign celebrating the Ku Klux Klan on the side of his barn facing the road.

Wow, I remember thinking. Pretty much right nearby to me. And in this day and age.

The article really got under my skin; I couldn’t stop thinking about it. Finally, I gave in to it, driving out to St. Amant one day to see the sign for myself. This was long before most of the world had even heard of a personal GPS.

When you first leave Jefferson Parish going west, it’s ugly, an endless urban sprawl, the path of the “white flight” from downtown New Orleans over several decades. And then it’s kind of sudden: You find yourself on a long stretch of concrete bridge high up over miles of soft ground, brackish water, stinking muck, swamp trees and bayou shacks. From this lofty cement perch, it’s easy to forget: That’s the floodplain of the Mississippi down there. That’s the birthplace of the blues.

About 40 minutes out of Metairie, I was stopping at a little store just outside of St. Amant to see if anyone could give me directions to Frederic’s house, telling the guy behind the counter that I was a reporter from New Orleans. That was a bit of a stretch: I was then an editorial assistant at a nonprofit arts magazine.

But “reporter” did the trick. The store clerk knew where I wanted to go even before I told him. It turned out to be close by.

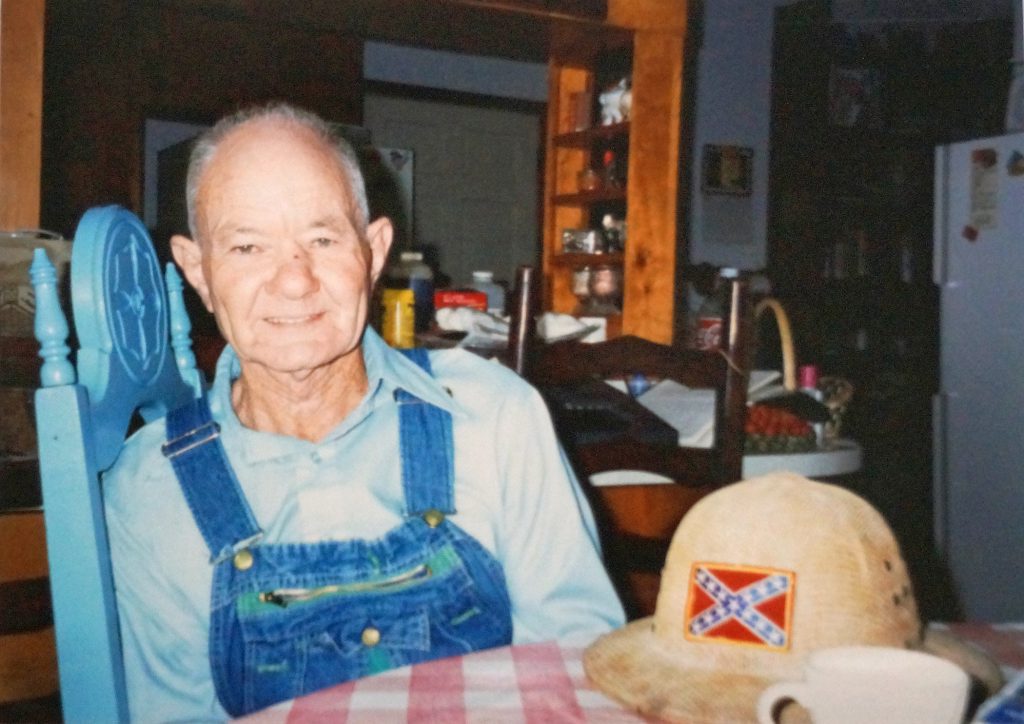

Soon after, as I stood beside the road in a quiet, rural, middle-class neighborhood, staring across a wood-and-wire fence at the bold words on Frederic’s barn, a dark-blue pickup pulled up in the driveway of the adjacent house. It was Frederic and his son, Denny, though they didn’t pay me any mind, really – people must have stopped there all the time. What the hell, I thought, and walked over to meet them.

There were standing beside the truck now, looking my way: Frederic, feisty yet affable, and barely more than 5 feet tall, was wearing denim overalls and a little straw safari hat with a miniature Confederate flag sewn into the front. Denny, 31, was slightly taller, with thick, extensively scratched glasses that made his eyes look too big; an unfortunate set of teeth; and what struck me as all the sense of one of the fenceposts I’d just been leaning upon.

Frederic told me how proud he was of that sign. Denny just grinned, an unfortunate occurrence.

The sign took up about a third of the long, gray barn. Its background was black, the letters white.

A few minutes later, and I was sitting in Frederic’s kitchen, and his wife was fixing me coffee. On the wall by the window, a framed, signed photo of David Duke – the former Klansman who’d staged a well-publicized run for Louisiana governor in 1991 – smiled down on an oversized, dog-eared family Bible lying open on the table.

I recorded my conversation with the Frederics on a hand-held Sony Walkman knockoff. I didn’t check the batteries first. They were, it turns out, nearly dead. I now have a tape full of Alvin interviewing a couple of Racist Chipmunks. The word “nigger,” even when squeaked, isn’t a funny sound.

But sitting at their table that day, I couldn’t help thinking to myself that they should seem more, well, evil. I’ve realized since that maybe that was the true evil in the situation.

The first thing that crossed my mind as I was preparing for my interview with the venerable bluesman, and read in some press clippings about Guy’s childhood friend Craig Fedducia, was that barn in St. Amant, and that denimed little bigot, Sam Frederic.

I went back and forth on whether to bring up Frederic, fearing a reporter’s nightmare, silence at the other end of the line. But Guy – a consummate gentleman – quickly puts you at ease. So the moment I started feeling comfortable with our rapport, I not only gave I to what was on my mind, but I talked the Frederic experience into the ground – not just about the sign, but about the coffee, the Bible, David Duke’s smile. I didn’t want Guy to miss my point. He didn’t need the small details to get my point.

And then I asked him a question I had no right to, receiving an answer I hardly deserved.

How could a man like himself, who has so much love for others, keep from losing faith, when there are still so many Sam Frederics left in this world?

“First of all,” Guy says quietly, “we got this in all races, on all sides.” He pauses, and above the tape static, I hear him draw a deep breath, yet one more thing that escaped me during our actual conversation. “Let me put it like this: From the beginning of time, we’ve had this problem. We’ve got this sickness with ‘I’m too big, I’m too little, I’m too tall.’” He laughs softly. “You know, ‘I’m too white, I’m too black.’

“I was brought up by my family to not let things like this get me. And I don’t think me, you, or my children or grandchildren are gonna live out the fact that we’d love to see this world loved by everyone, and everyone loved by everyone. But I just don’t think that’s gonna come – because there’s so much hatred here, man, jealousy and hatred. Jesus Christ went to the Crucifixion just because of that. I don’t think they did [Jesus] bad because of who he was. They did it to him because of jealousy and hatred. And as long as we live, you gonna see that sign out there, and not only by a white man.

“I don’t hardly watch them, but every once in a while, my wife has on these talk shows. And they have blacks up there, man, feel the same damn way. I don’t know if they got a flag or some sign they painted on their barn or garage, but I’m sure they would if they could.

“That hatred,” he adds, “it’s gonna be here.”

I rather press the point, because apparently being naïve and being arrogant are not mutually exclusive. I say then that I’d always thought music, at least in some small way, might help to change that, to break down some of that bad feeling.

“It does in one way,” Guy begins. But before he’s able to expand on that thought, he’s sidetracked by another, more powerful one. Buddy Guy may have been brought up to not let this kind of thing get to him, but he’s an exceedingly gentle soul. It gets to him, all right.

“I bought a home about 12 years ago,” he says, growing even quieter, “and I think I was the first black person moved into Country Club Hills, which is a little suburb of Chicago. And one day I went there, and some eggs had been thrown on my house. In the long run, whoever threw them didn’t know who I was. [And then] the Sun-Times wrote an article with a big picture of me. One of my neighbors come over and said, ‘No.’

“He was just looking,” Guy continues, “and saying, ‘No.’ And then he came over and started cleaning the eggs off the house.”

That’s the point where I laughed: Fuck the Sam Frederics of the world, here at least was a little justice.

And that’s where Buddy Guy began to cry.

“I told him,” Guy says emotionally, “’Don’t!’ Because when I come out in the paper as Buddy Guy, I was supposed to be different.

“And that’s not fair,” he continues, a sob cracking through his voice.

When Buddy Guy sings, it’s a mighty, boisterous thing. And when he shouts like he also does so well, on a cut like “Damn Right, I’ve Got the Blues” from the 1991 Silvertone album of the same name, it’s easy to forget how that big voice of his can bend with the kind of subtle emotion that makes knees weak. But listen to Guy from the ’68 recording of his own “You Were Wrong” on This Is Buddy Guy!, and you can hear the weeping in the back of his throat, the little catch that says it even plainer: Damn right he’s got ‘em.

When I listen to his records now, I can often hear nothing but the crying. I suspect it’s because those other tears, on the tape of my interview with him, kept me awake for the next two nights after we talked.

“Just because I was a musician,” he continues, still weeping softly, “why wash down?” He pauses again, to collect himself. “That’s the way people are,” he says finally, his voice a little firmer. “If you’re supposed to be something special, then you get special treatment. I don’t like that.

“Just treat me as I was before you knew who I was.”

But Buddy Guy isn’t, y’know, just some guy. Once you realize that, however slow your recognition, it’s kinda tough then to pretend otherwise.

In December 1993, Billboard presented Guy with its prestigious Century Award, in praise of a lifetime of creative achievement. And at the time of this interview, Guy was looking at probably a third Grammy (he got it), for his 20th album, the outstanding Slippin’ In (Silvertone, 1994), a vital slice of Chicago-blues history in the here and now.

Industry praise is almost always too little too late, a public penance after years of shameful neglect. In light of Guy’s years of obscurity on the popular front, it’s easy to forget that his adopted hometown became the town for electric blues in no small part because of him and his pioneering forays into feedback and distortion, his balls-to-the-wall solos, machine-gunned chains of staccatoed notes that led Leonard Chess of Chess Records – to which Guy was signed from 1960-’67 – to repeatedly denounce Guy’s playing as “motherfucking noise.”

Chess held the minority opinion; Guy was one of the most in-demand session players in those early Chicago years. And make no mistake: The tough, tender kid from Lettsworth almost single-handedly redefined the role of the blues guitarist in a band format, paving the way for innumerable young six-string guns of the future.

Guitar gurus – Clapton, Jimi Hendrix, Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck, Carlos Santana, Steve Miller, Eddie Van Halen, Robert Cray – would speak his name like a prayer. Hendrix, in fact, once asked Guy if he could record the bluesman’s concerts so that he could learn from them (Guy was playing behind his head and with his teeth in bursts of Guitar Slim showmanship before Hendrix was even old enough to drive; and in 1986, a professional Buddy Guy disciple rumored in 1960s London graffiti to be God himself called Guy “by far and without a doubt the best guitar player alive.”

And not shortage of popular rock singers – most notably, Led Zeppelin’s Robert Plant – have spent whole careers trying to mold their voices into his.

Add to that the fact that Buddy Guy has not only shared stage and studio with the great bluesmen of this age – Muddy and the Wolf, Sonny Boy Williamson, Little Walter and many others – but he also played on Water’s seminal 1963 Folk Singer album. There’s also no misinterpreting Waters’ actions in those last years of his life: The Chicago-blues torch was passed to his adoring disciple.

But it isn’t a torch, Guy asserts, “It’s a load.”

Among the living, only B.B. King and John Lee Hooker are in the same league with him. So Mr. Buddy Guy will have to forgive me, but a little special treatment is in order.

And yet Guy remains, above all, unflaggingly humble. I accuse him of it, and he laughs. “I’m still a little country boy that used to wouldn’t talk to you, man.” (Legends can stay stuff like that.) “I’m still shy myself.

“I never felt like I was anything special,” he continues, “and still don’t. I think when [you] learn something, or God gives you a talent, you share it.”

But that talent, he reiterates, doesn’t make you somehow better than your fellow man. Treat me as I was before you knew who I was.

“It didn’t make me a different person because I learned how to play the guitar,” he asserts. “And it didn’t make me a different person because I won a Grammy, or because I won that Billboard award. I’m still the same person my mama used to tell, ‘Never forget where you came from.’

“God didn’t give me [a talent] to say, ‘I can give you something to make you different from somebody else. [Instead], I give you this to … make people laugh and enjoy themselves for that moment. I give you the gift to them, and you give them the enjoyment of listening to you.’

“And I’m having just as much joy givin’ it as they is receivin’ it.”

Inarguably, there’s more joy for Guy now than even a few years ago. Before his Chess Records deal, he experienced some mighty lean times, and when that deal fell through in ’67, there were plenty more lean times still ahead. That same year, in fact, Guy was forced to take a job driving a tow truck.

“I couldn’t make enough money to take care of my family as a guitar player,” he explains.

But his love of music would never let him quit outright, not through the nights of playing for food and having to sleep outside, or the slightly better nights of hotel rooms without doors.

“I was so crazy,” he says. “I didn’t have sense enough to say, ‘I don’t like this stuff.’ I didn’t have sense enough to say, ‘I’ll quit,’ ‘cause I loved it so well. Now, a young person can say, ‘Shit, I’ll learn it and get rich.’

“When I learned to play guitar,” Guy continues, “I didn’t learn for money, [but] for the love of the music. It wasn’t no such thing as lookin’ up [at a musician] and sayin’, ‘One day I could live comfortable and be travelin’ from city to city around the world, gettin’ paid for what you do.’ And then, all of a sudden, it happens. The British guys came in. And in the ‘60s, people went to payin’ good money for [blues music]. Record companies went to sellin’ millions of records. And that was the time when you sold a million records, you was the biggest thing out there.

“I remember that [when I] was a youngster, if you sold a hundred-thousand records – [like] Nat King Cole, Patti Page and people like that – you was a big star. Now if you sell a hundred [thousand], they liable to tell you, ‘Shit, I can’t do nothin’ with you, you go!’

“I still think right [up to] today, the way I play and how I play is not for the money. It’s for the way I love the music. And then, if I get paid, fine.”

These days, Buddy is getting paid, and not all badly, at that. And, at an age when most of us are consigning the best part of ourselves to our long-faded youths, he’s having the time of his life.

“Oh, man!” he says in ready agreement. “If you had to be me to know how I feel!”

You can’t go home again – or can you? Time inevitably steals those places we cherish most from our childhoods, but what if those bygone days weren’t all that rosy in the first place, suffused instead with finite, color-fast friendships, and riots over school integration?

“You know,” says Guy, “I’m going to New Orleans to play the House of Blues over the weekend. And I’ll be dog if my whole family don’t say, ‘Is there any room?’ But there’s no room left. My manager can’t even stay in the same [hotel] room with me. And they was sayin’, ‘If I get a room, can I come down there?’ I say, ‘What you want to come down there, you hear me play in Chicago?’ They say, ‘No, I’m goin’ to eat!”

His family, Guy explains, is recalling past trips to the great delta state, when they would walk in the mornings by “the restaurants and these homes … when these people be cookin’ this original bacon and grits and stuff like that.

“My wife [keeps] sayin’, ‘You nut. How did you ever leave [there]?’ I say, ‘Girl, when I left [there], things was different. You know, you was ridin’ in the back of the bus, and all that stuff. It was a whole different story than it is now.’”

With some stories, you can never guess the endings. Guy is now giving some thought to buying a little piece of property back in rural Luziana, where the people say hello when they see you coming, where the summer lasts almost all year long, and where you don’t have to get up before the crack of dawn, before the waves of traffic overtake the streets, to catch the only breath of fresh air all day.

“My wife loves it so [down there],” Guy explains, “and I’m not a baby anymore. And I still love my gardens; I’m able to buy some land now, so I can, say, get me one of those little garden tractors. And I love my beans, and cornbread and greens and stuff. I love my dogs to run free, and not with a leash around their neck. And if I live, and stay healthy enough, I would like to go down in one of these January-months, when it’s below zero in Chicago, and sit on my porch and read my paper.”

And if there’s a small article tucked toward the back, about some new Sam Frederic or other – be he white or black or whatever – blighting up some other rural byway with overblown acts of bigotry? So be it. Such things are now the exception, Guy notes, not the norm.

“Please believe me,” he adds warmly. “The tunnel looks much brighter at the end than it did a few years ago.”

Buddy Guy, a big-hearted giant in a world of small advances, would most certainly deny it, humble to a fault, but he is himself a wide swath of that goodly light.

On Oct. 26, 1998, I did a phone interview with ebullient, genre-defying Austin, Texas, singer-songwriter Sara Hickman for the folk-music magazine Dirty Linen. The publication had made a rare request of me – that I inquire of Hickman about a specific subject, her considerable work on behalf of orphan children in Romania.

I had some real personal investment in meeting Dirty Linen’s request. I’m of Ukrainian heritage, just two generations removed from living in abject poverty way up in the Carpathian Mountains, the same chain that also runs through Romania. I explained my personal interest to Hickman, and before it was over, she was pouring out her heart to me, and openly weeping. It was an agonizingly tender experience, and I found myself apologizing to her for leading her down such a painful road, and bringing her to tears. And somewhere in there, I mentioned my 1995 interview with Buddy Guy, and the Sam Frederic story, and the crying that happened then, and how it had haunted me for days afterward.

Hickman said: “I think perhaps you should be grateful that he trusted you. He wept in front of you, he was honoring you. … He could have certainly said, ‘I don’t want to talk about it.’ But he thought that you cared.”

Then she suggested something that had never once occurred to me, that Guy was giving to me as opposed to that I was taking from him.

For several years now, I’ve regarded my interview with Guy as an example of how to truly botch things up, of a foolish young writer stumbling, and falling, in the path of a giant. Hickman gave me a whole new deck of cards to work with, and I’ve started slowly to reshuffle the truth.

<32 post likes from original blogsite>

Comments

This is, hands down, one of the nicest reads I’ve yet to come across ?