Y’know how the most mundane of things can drop you smack-dab in the middle of the most poignant of memories? No? Well, get to be my own sparkling young age, and trust me, you will.

For now, let us begin:

With a text received just the other day, from an insurance company. Not some business I am in any way connected with, mind you, nor even one soliciting me to buy a policy. Just an insurance company, chatting me up.

Now, I am no great fan of the insurance industry, particularly as it relates to this country’s health-and-wellness sector. And that, by the way, was me being unusually politic, in light of what I currently do for a (partial) living, and my also now seeking additional work.

Anyway, I do hate to use the word “loathe” on such an otherwise lovely afternoon.

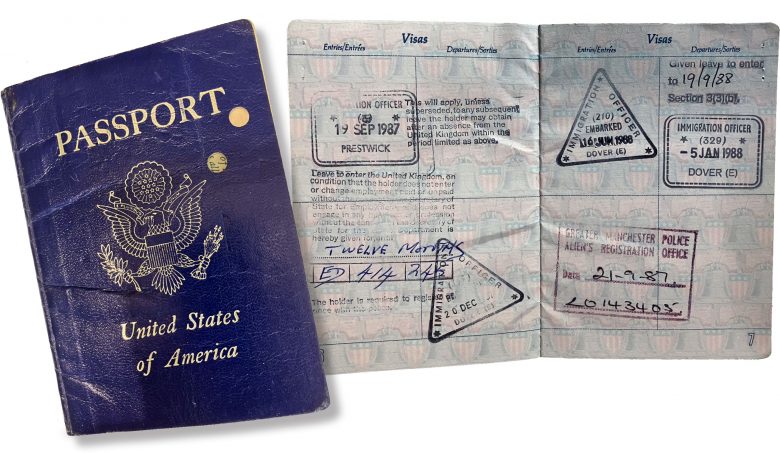

And all of that, some 25 years on, not unexpectely brings me to this:

In 1988, the British National Health Service, the opposing pole to America’s health-insurance “health” model, literally saved my life. And when I say literally, I mean, yes, literally.

Now, going back just a bit further:

To when I was traveling/overindulging across mainland Europe with a couple of road-met fellow downward-aspiring Americans. Each of us was in hot pursuit of lesser/cheaper means of personal de-escalation, and I managed instead to get a spiffy little case of dysentery, or else an intense bout of food poisoning, in Barcelona, Spain, in between peering at Important Art in Important Places, and scarfing down heaping plates of paella, and also taking the drugs, and drinking the drink, and also, perhaps, taking the drugs.

Which is to say it’s all good times until the shit hits the … well, anyway.

My travel friends, one of them the same fab guy who, after all these years, and so much water under so many bridges, and who back then went by the family nickname Tom, and whom was first met in Madrid, when I was with second travel amigo Will, while the two us were baked, in whatever grand fashion, in front of some famous painting the name of which I cannot now recall, and after Tom’s own fight years later for sobriety in the face of a relentless addiction, and who is someone I, well, remarkably, someone I still hold close …

And wow did that overworked sentence completely lose itself as it tumbled down the purported primrose paths of memory, completely out of sight of all things insurance.

So back then, in our for-now deductible-free direction, to Tom, and briefly also to Will, a chef from Chicago, whom I first “met” by stepping over a scraped-up, passed-out, backpack-topped pile of him in front of the San Sebastian train station. Will split from our trio at some point, now lost to memory, while Tom would later refuse to leave me bathroom-barricaded in that dingy Barcelona pensión we’d picked for that night, loading leaky Frankie that next day onto a train that was, as European trains sometimes are, absolutely brimming over with humanity; in memory, I sometimes picture train cars so over-packed that stray arms and legs hung out of the windows. And me, the whole trip north out of Barcelona, wanting to hurl, and direly needing a vacant baño every time it seemed some little kid was running in ahead of me, to spend more time fiddling with the lock than actually using the effing toilet.

Speaking of those, y’know, precious youngsters, one of them I came into contact with that day apparently had chickenpox. With my resistance shot all to hell, and my body ignoring outright that I had already had the blistery malady as a kid, my sorry physical state simply opened wide its proverbial arms to the adult-improbable contagion, shouting, hey, sailor, wanna come on back aboard?

Pro tip: Do not get chicken pox as an adult. It’s no great party having it as a kid, sure. But as an adult? Just don’t, that’s all. Don’t.

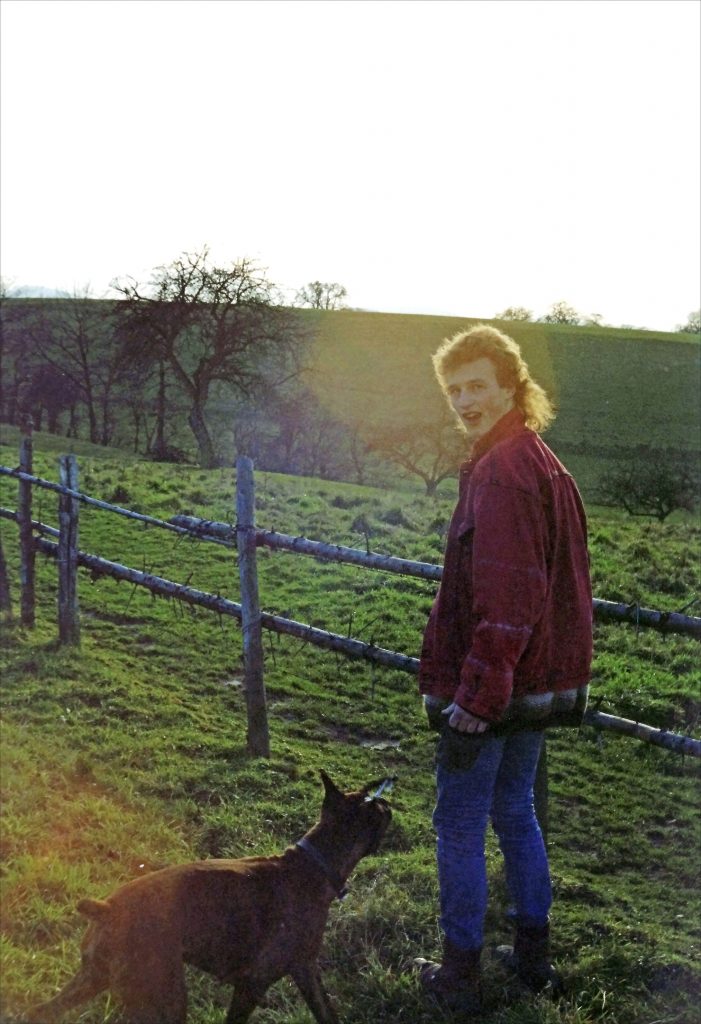

Tom and I parted ways coming out of Spain; I was heading up through Switzerland, back to my friend Bertram’s home in Rimbach, West Germany (we’re that long ago here, yes), at the foot of Bavaria’s Hoher Bogen Mountains, to hopefully recuperate for a few days; I had previously stayed with him and his family during part of the winter holidays. Bertram, an exchange student in my own high school a few years before, and an absolutely sterling guy, was actually off at some work training at the other end of the country. His family was extraordinary, though, taking me in again anyway, and taking care of me. Phenomenal folks.

Bertram’s dad always gave me way too much beer at dinner, refilling my glass, and again refilling, and once more … with superb Ayinger lager, in part as an excuse to be able to slide his own additional consumption by the missus. I was never able to dissuade his re-brewing, nor his ready encouragements to austrinken, austrinken! So, not wanting to be a rude guest, I ausgetrunken as instructed, and wow is it beginning to spin a bit in here …

I left the table a tad drunk every single evening I stayed with them.

About 10 days out from that fateful train ride, and right on target for childhood pal varicella-zoster to pustule on up and say howdy – and also after my meeting back up with Tom, by absolutely wonderful chance, on an Amsterdam hotel boat I’d recommended to him about a week before, for us then to, y’know, jointly embrace that fantastic city’s most noted American traveler’s charm in those weed-lean years before legality was even a proverbial pipe dream in our own country, and having one helluva time, then boy howdy, well …

I must be fucking exhausted, I thought; I’m suddenly getting all this acne, really crazy acne. Big, bubbly bumps, all over my face – and not just on my face, but also on my neck, and on my shoulders and arms. I’ve seriously gotta slow down. And I will, as soon as I get to Perth …

I first noticed the lesions while on my ferry trip back to Dover, England, from where I’d departed nearly a month prior, then totally in the bag – that is, my own soon-to-be projectile-vomiting-in-front-of-horrified-French-passengers bag. From Southern Comfort, no less, that sickly-sweet whisky blend I cannot smell even today without hints of nausea and regret. I had pounded a whole fifth of that garbage, a whole fifth, idiot that I too often was, before staggering onto the Calais-bound ferry, and then, instead of soon simply keeling over dead from alcohol poisoning, puked pretty much the whole of it back up, luckily in the ferry bathroom, earning a hangover unlike anything I have, thankfully, ever experienced since.

I had by then been living in England for about nine months, as a student at the University of Manchester, and had always intended, upon my return from my final Continental ramble, to head north, into the Scottish Highlands, bound ultimately for the Orkney Isles, the very tip-top of the country, because I adored the King Arthur tales as a kid, and those exotic knight names Gawain, Agravaine, Gaheris, Gareth …

In southwest England, possibly in the town of Ashford, I got stalled in my hitchhiking efforts, attempting to snag a ride out of what I knew to be a truly boneheaded spot, just above a bus stop, the road itself bustling with traffic. It had been the only place I could find with any room for drivers to pull over, and anyway, I didn’t have it in me to walk any further with my bulky pack at that point. My body had started to feel like it was humming, like I was some human tuning fork tapped to vibrate with fatigue.

Finally, in one of the two great saved-my-ass lifts of my short but illustrious hitching career, this guy pulls over and tells me what is obvious, that I need to get further out of town if I hope possibly to get a ride going north. He offers to take me to a better spot; his job is up that way. We talk on the trip, and in listening to my plans, he says:

I work for a trucking company. We go up into Scotland a couple of times a week. I can put you in a lorry later today, for an overnight trip into the Highlands.

And he did.

My “uncle” Joe, a dear family friend, now alas 10 years gone, had a cousin then in Scotland, in Perth. I was to contact her if ever I got up there. I figured I could maybe stay with her for a few days, something I had been reluctant before to consider, but now I required some serious rest, I thought, to recharge my batteries, so I could push on north, to those gloriously named ghosts of the ancient sons of Dunlothian.

I’ve since felt really lousy for that lorry driver, because I looked by then like absolute hell, and was acting increasingly peculiar. I not only had plenty of obvious lesions, but could also barely keep awake whenever I stopped moving and, feeling constantly overheated, was sweating accordingly. I can’t remember even talking to the driver during that trip, drifting off into unsettled sleep soon after we set out.

At some point some hours into it, I came to, feverishly disoriented, not sure immediately where I was. The new sun was just then cresting the mountains, as I have described that uncanny moment elsewhere on this site:

The overnight driver had just crossed through a mountain pass, out of deep darkness into sudden morning, with the sun popping up from between the peaks to our left, revealing a sprawling loch stretching back to the base of the mountains. The water was, from bank to bank, the very color of the rising sun. The color, that is, of fresh blood – a whole mist-topped lake of brilliant red blood. The lorry driver never commented on it, assuming he even noticed it; he drove that same route several times a week. Nonetheless, that startling sight has profoundly unsettled me now for more than 20 years.

So was it my fever? Or was it real? I don’t care. I saw it, either way, and now it’s mine.

We came into Perth shortly thereafter. I only vaguely recall getting out of the truck that chilly morning, way too early yet to be contacting anyone, especially someone I’d never met, and knew virtually nothing about, and whom I was nonetheless hoping might offer to put me up for a bit. I found a nearby public park to wait it out, settling onto the ground and propping myself against my backpack.

And promptly passing out again.

I came to with the sun up a bit higher, and an older gent in a hat and long coat standing there looking down at me. A small dog on a leash – a Scottish terrier, no joke – was straining to get a good sniff at me.

The man, frowning, said: “Are you OK?” He seemed to be dreading my answer, fearing maybe that he then might be called upon to do something.

To which I replied, and I can still distinctly hear myself saying it, “No, I really don’t think I am.”

Because by then, even with my dogged attempts at self-delusion, it was clear something was seriously off with me, that I needed medical attention. I didn’t get how the whole National Health thing worked, however, and assumed, quite wrongly, that I had to go all the way back down to Manchester to see someone, since that’s where I’d been living.

I don’t know what else the Scottish gent and I might have said to one another, though I must have offered enough to satisfy him that his attentions were no longer required, as he soon walked on.

So I dragged myself back up, to begin reversing my course. Maybe fittingly, or at the very least, perversely, the outward weather had also begun heading south, going from cold to now a bit rainy, then constantly rainy and, yes, still cold. In this way I launched my sad-sack, thumb-out retreat back to Manchester, trying not to wonder too much at what was going on within me.

I don’t remember a lot of the rest of that day, beyond standing in mud along a rural two-lane in what had become a steady, hard rain. After quite some time, I caught a pity lift, the runoff from my clothes puddling at my feet in the small car, with the driver very graciously ignoring it. I ended up later at a family-run inn in some smallish town just to the other side of the English border, where I spent almost all of my time in bed. I felt too listless, and too pathetic, to even flirt with the female proprietor’s fetching daughter, who was around my own age, and who likely would have ignored my Ugly American advances in any case.

I haven’t the slightest recollection of finally arriving back in Manchester, much less of how I got the rest of the way there, only of that long slog along Oxford Road from downtown, to reach university housing, and to find Andrew, my former flatmate, still living there. I can’t imagine what he must have thought upon seeing me. He was always an ostentatiously tidy fussbudget of a guy.

Andy located a doctor’s office for me in that part of Manchester, insisting that he get me a cab there, but no, pigheaded Franks will invariably do pigheaded things. My walk that couple of miles further down Oxford Road was agonizing; my stomach had been flipping itself into painful knots for at least the past 10-12 hours – which had become my overwhelming worry, and what I by then wrongly assumed was the source of my overall physical problems, increasingly unavoidable blisters be damned. Once in the clinic waiting room, soaked in sweat, I was practically writhing in place trying to stay seated.

The visit with the NHS doctor was, in retrospect, pretty comical. I proceeded to tell him how I’d been getting more and more rundown while traveling, and these sharp pains in my gut had brought me in to see him.

You have chickenpox, he said.

I said, no, that’s not it. Anyway I had that as a kid. See, I’m here about these awful stomach pains …

To which he said, bluntly: Dunno what’s going on with your stomach, mate, but you have chicken pox.

Only he probably didn’t say “mate.” I just want him to have, that’s all.

No, I protested once more, see, I had that as a kid …

Well, you now have it again, he said bluntly. And you are going into hospital. Toot sweet.

Here again, pretty sure he didn’t actually say “toot sweet.” I merely love the idea that he might have, as Brits reportedly used to back during wartime, in the siren-saturated shadows of bombed-out buildings, between plenty of buck-ups and tut-tuts, and all those stiff upper lips. Because it’s my memory, goddammit, and it could really stand a charming detail about now, since I know where it’s going from here. And it ain’t charming at all.

The NHS doc conceded to give me a couple of hours to get my affairs in order, with a demand of me as to where I was going when I left there (he actually wrote down my answer), and the promise that I show up at the hospital or he would send authorities to come find me, and then put me there. So I set out back down that same long road, back to Andy’s flat, to retrieve my stuff, which he’d been gracious enough to let me store there, and to say my final goodbyes to him. He was a really good one, that one.

I waited then, slumped on the curb in the alley that drew up to the back of university housing, barely able to keep myself upright, and leaning forward onto my pack, which I’d positioned between my knees. The clinic had called a cab to meet me in that spot a bit later, to take me to the hospital I’d been booked into.

A man kept looking out his window at me from across the narrow street. Finally, he came out and asked if he could help somehow. I told him to please to stay back, as I had chicken pox, and was waiting on a cab to take me to a hospital. He said he didn’t care, and would I like to come in for a cup of tea while I waited? It might make me feel a little better …

I was too afraid of infecting him or anyone else who might be inside; I had no idea back then how incredibly slim the odds of that. So I said no, I’d be all right, thank you, so very kind of you, etc. He persisted in his attempts, but finally let up, saying he would keep checking on me, which he did, through the window, and poking his head out the door a couple of times to yell to me, until my cab finally arrived.

Simple human graces. You just never know where you’re gonna find them.

In retrospect, I feel absolutely the worst for that poor cab driver, a Caribbean guy, full dreads, thick accent, who took one long look at me, upon hearing hospital, and grew quiet; there’s no telling what he imagined he’d just picked up, Joe Leprosy or Typhoid Yankee Tourist, Lord only knows what. He said barely word one the whole trip, probably scared even to breathe with me in the backseat, with no partition between us.

I was checked into what I believe was a refurbished old military hospital, with wide grounds and a series of paved walkways that I would later haltingly traverse as I tried to regain my strength, though that’s jumping way ahead here. For the next several days, it was all constant attendance from concerned nurses and doctors; seemingly every time I got out the bedpan, and prepared for a wee (we’re still in Britain; wee it is), a female nurse would invariably pull wide the curtain separating me from the hallway, and step briskly to my bedside for whatever medical purpose of the moment.

I’m honestly not sure how I managed to wee, as it were, that whole time, until I could get out of bed a couple of days later, itself a wholly exhausting undertaking, to go into an actual bathroom.

I remember two other things very vividly from my stay there:

First, after they began administering an IV-based treatment, which the doc told me would actually speed up viral activity in my body, I experienced pain in my head on an order I could never even have imagined, nor, fuck me, ever wanted to. Opening and closing, even moving, my eyes; drawing anything but the shallowest of breaths; turning my head but a fraction of an inch – searing, hideous pain. The nurses set me up that first day on a morphine pump, which I rode like a Jeopardy champ at the answer buzzer. I don’t know now how long before that pain finally started to subside.

Certainly not for a while, which brings me to vivid memory No. 2: During my first evening there, with me essentially pinned in place by my pain, like some pitiful still-living still-life, I had a most unsettling soundtrack: hours of distressed, wet wheezing from an old man on the other side of the accordion partition separating the two of us.

Then, late that night, the wheezing just. Stopped.

I next could hear staff racing to the man’s bedside, and a jumble of talking. Shortly after, the squeaking of bed wheels on tile floor, fainter as the bed was moved further down the hall. Then, silence.

Which immediately had me thinking: Holy freaking hell, that poor bastard had some heinous respiratory illness, and was right here beside me, in a hospital for isolation patients, and that flimsy partition doesn’t even reach to the ceiling, and he just …

The thought bounded right past my flagging mental defenses, straight through the fiery-heartbeat pain in my head: You’re gonna die here, bub, just like him. You are going to die.

I didn’t, clearly. But I damn sure nearly did.

What happened after, following my eventual release from the hospital (I have no clue now how long I was in there), in the very weakened week prior to my return to the States, was ridiculous, and kind of pathetic, and also often hysterically funny, involving people who were ultimately very kind, even in their wanting not a single thing to do with me. So let’s just leave that set of tangential memories lie …

On that long plane trip back across the Atlantic, I had an aisle seat opposite a loud, vividly blond, thirtysomething American, who introduced himself as Whitey, and who worked most of the year in a gated compound in Saudi Arabia, raking in beaucoup bucks doing whatever in hell he did there. This Whitey fella was headed back to his family’s Midwest home on vacation, aggressively getting blotto on mini-bottles of airline liquor. I shouldn’t have given in and joined him, as he convivially kept asking, not for one drink, or two, or then I don’t even remotely recall. I was hungover and sweating through my clothes while later wilting outside in baking late-summer New York City heat, waiting for the shuttle to my transfer flight out of La Guardia, bound in queasy fashion for the uncertainty of whatever was next.

I learned from my dad years later that the National Health physicians had given me an experimental drug, something not then, nor for all I know possibly still not, available in the United States. Something my old man, himself an expert on infectious diseases, simply marveled at. He sang the praises of the NHS many times in his own final years, once he and I had at long last grown close, noting that their giving me that drug had, in no uncertain terms, saved my young, dumb life. I had developed advanced viral meningitis, and he and my mom honestly thought I might be a goner; NHS staff had actually contacted them to say they should consider getting over there, toot sweet.

OK, again, no actual too sweet. Sorry.

Helluva memory though, even 25 years on. And perhaps undeservedly poignant to now bring us to this, just this:

I have recently posted my updated résumé on several larger online job-search sites, as I seek some meaningful new employment. And who is it that uniformly keeps reaching out to me, unasked, via chatty emails and text messages? One insurance company after another, each offering me a “new career path” in their ever-expanding suck-hole of an industry, which routinely allows people to die, or become financially destitute, in the act of simply trying to stay alive.

So with every bit of my own life that British nationalized health preserved for me all those years ago, I say now: Shove it, you greed-baked demons, you wretched disease profiteers. Shove it, right along with my deductible.

Shove it, toot sweet.

Comments

An excellent read, as always. Well done, kudos, and all that. Had to read it twice, in fact, to make sure I hadn’t missed a single word…. almost felt like I was a bug hanging over your left shoulder, watching you get sick, and all that… Dunno what kind of bug …

Now, a heads-up: For all those folks, especially medicos, that insist you can only get chickenpox *once* …. ‘eff ’em. I’ve had it thrice myself, thankfully all as a young kid in Hawaii. Twice hospitalized in Tripler Army Hospital in Honolulu … back when it still hadn’t had a refirb since WW2. Not fun at all; worse, I can well imagine, as an adult. The heads-up: I’ve been told by several actually intelligent medicos (as opposed to the average lot), that if you’ve had it more than once … that fun reunion you get as an adult, Shingles, will not likely be a one-off as most folks get. I’ve had it off and on since a tad over 50, so …. not quite two decades now. Of course, it likes to show up when you least need it, like when all those goddamn stressors are hitting you at once …. Shingles loves to kick a guy when he’s down (expand out, natch, for those that are non-guys.) There are, I believe, two different vaccines that are *supposed to help.* I’ve had ’em both …. if they help, then god help me if I hadn’t had ’em, ’cause I’ve still gotten seriously stricken… and you KNOW how I feel about invoking god …

One last suggestion: Avoid — at all costs — working for those health insurance companies. My mother-in-law retired from one of the big ones a couple years back, after working in the industry nearly 50yrs. She was a senior account exec, made more than some doctors make, but had no time of her own. They finally told her she HAD to retire at 76, so she felt kicked aside. She made a lot of money … because she gave all her spare, and not-so-spare, time to her clients. She gave her life to the company in exchange for cash … and now doesn’t know what to do with herself, because she never developed any hobbies or interests besides work.

Then her worthless son, a guy with a Masters in something something health & fitness (though you wouldn’t know it to look at him now), ends up selling health insurance and … annuities, for the Knights of Columbus …. ONLY to members of KoC … which, in these parts, is a pretty small cohort…. ie, he’s always broke. Which is, of course, where all of mom-in-law’s money went over the years, keeping his sorry arse, and by extension, his wife and kid’s arses, with a roof over their heads (and arses.) BiL, of course, has no life because … yes, work first … as if it actually paid the bills. It’s just Amway for insurance…. the upline makes the money, the peons do the work…

Knowing how, y’know, you love to actually HELP folks …. I’m guessing it’d only be a matter of time you’d go apeshite ballistic if you were working for a health insurance company where you constantly have to say “well, IF you bother to really read your policy …”

Nah …. you’re too good for that. Dunno what’ll come up, but Imma gonna muster forth my best juju so something dandy comes your way. All you need to do … is recognize it, eh?

So great to see Bertram again!!

Author

Only wish I knew what had ever become of him!

I may have actually found the Chicago chef I mentioned, now working at a restaurant up in Canada.